|

|

|

|

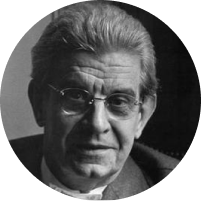

Le 21 juin 1964, Jacques Lacan fonde son École de psychanalyse (l’École française de psychanalyse) dans le but d’assurer la formation du psychanalyste, la transmission de la psychanalyse et de reconquérir le Champ freudien. La Nouvelle École Lacanienne (NLS), créée en 2003 par Jacques-Alain Miller est l’une des sept Écoles fondées dans le cadre de l’Association Mondiale de Psychanalyse (AMP). La NLS est membre de l’EuroFédération de Psychanalyse (EFP) qui regroupe les quatre Écoles de psychanalyse en Europe orientées par l’enseignement de Freud et de Lacan.