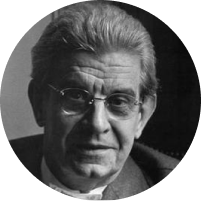

Three Questions to Jacques-Alain Miller

by Corinne Rezki*

In 1946, in his “Presentation on Psychical Causality,” Lacan, having already perceived the risk for psychiatry of searching for the cause of madness in neurology, described the decline of the psychiatric clinic. Would the equation therefore be: “everyone is mad + neurological cause = depathologisation”?

Contemporary depathologisation is not simply the consequence of the dissolution of the clinic due to the DSM and the promotion of medication as the universal key to “mental disorders”. It proceeds from the epochal shift in Western civilization, completely reconfigured by the system of radical individualism. We used to distinguish the normal from the pathological. Once the normal is deconstructed as “norm-mal(e)”, the pathological deconsists.

The pathologies of yesteryear are destined to become “lifestyles”.

Today's depathologisation is heir to what is already at work in “Presentation on Psychical Causality” of 1946, which is an existential depathologisation. It holds that madness – Lacan does not say “psychosis” – is a matter of the subject's freedom, of “the unsoundable decision of being”.

How can we not recognise in this an echo of the “original choice” on which Sartre’s Baudelaire is based, whose publication in Les Temps modernes precedes that of the “Presentation…” by a few months?

If Lacan takes his distance from the “metaphysical causality” attributed to the philosopher, he is nonetheless inspired to dissolve the so-called “organic causality” of madness in order to substitute it with the functions of freedom, its “minute blade” and its “ungraspable consent”.

Lacan makes no secret of his indebtedness to the existentialist school, acknowledging that he follows Merleau-Ponty's “phenomenological method” insofar as it “consider[s] lived experience prior to any objectification.” This gives rise to an initial distinction between the subject and the ego: the latter is but an objectification of the former.

It is demonstrable that the emergence of the Lacanian instance of the subject is correlative to a radical depathologisation of the psychic event.

In Seminar IV, on page 120, Lacan said of the madman: “the instituted world of the British Isles indicates that everyone has the right to be mad on the condition that one remain mad separately. Madness begins when one imposes one’s private madness on the entirety of subjects.” [translation modified]. What is the relationship between this definition and the Congress theme?

This is a thesis about England, and about the founding principles of tolerance of which it had given the world the theory and example. See Locke’s A Letter Concerning Toleration, its influence on Voltaire; Spinoza precedes it (Treatise on Theology and Politics).

The idea is that we agree to tolerate the other’s beliefs, on condition that he does not hold to them enough to impose them on me, nor that he tries to make me give up mine. Tolerance supposes that no one claims to communicate with an Absolute, and to love it madly. So, believe, yes, but in moderation – not absolutely. Believing is therefore ambiguous, because not believing is a moment of believing.

It follows that your belief is always particular to you. It cannot pass to the register of “for all x,” in other words, of the universal.

Nevertheless, it is in this solution of continuity, in other words, in the impotence of the particular to meet up with the universal, that Lacan, with Hegel, sees “the general formulation of madness” (See the “Presentation…”).

This contradiction is explained if we replace the half-flesh / half-fish belief, which is imaginary, with the delusional belief, which has to do with a real.

This is where the formula “Everyone is mad” is inscribed. This madness in question is that of each one, one by one. It has to do with fantasy insofar as it determines each one’s conception of the world – which is like no other – and his or her singular feeling about life. In that sense, it is a “private madness.” To collectivise it is to pass from fantasy to fanaticism.

Lacan was surprised that so many people attended his Seminar. As head of the School, he prohibited any group life in his School, which he left to others to run in a rather disorderly way.

This theme resonates with a burning topicality. What is the mainspring of the visionary character attributed to some of Lacan’s propositions? Is it rooted in the finesse of a logical identification of the tribulations of the parlêtre?

Lacan began by formalising the Oedipus in terms of the paternal metaphor, and by establishing the Name-of-the-Father as the master signifier essential to humanising and normalising desire.

Subsequently, he was able to note, in his practice, the disintegration of patriarchy and the promotion of the object a, there where the S1 had been. He extrapolated a new clinic from this and announced very early on, the overthrow of the old order of things in Western civilisation.

He was not enthusiastic about this prospect. The title of his Seminar XIX discreetly indicated this: an ellipsis followed by “…or Worse.” It was the Father who was thus elided. “Père ou pire” – “Father or Worse,” this is where we are.

Translated by Peggy Papada

Reviewed by Philip Dravers

*First appeared in Hebdo Blog on 4 February 2024.

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

New Lacanian School