of public service the journal of the New Lacanian School is”

Éric Laurent

On Jean-Pierre Deffieux’s “On reasoning madmen”

Jean-Pierre Deffieux’s “On reasoning madmen” analyses the seminal work of Paul Sérieux and Joseph Capgras for an English-speaking audience. Sérieux and Capgras were two major figures in French psychiatry whose 1909 publication, Les folies raisonnantes, which was considered a “masterly” work by Lacan, provides significant background to some important points in Lacan’s own understanding of psychosis.[i] Their analysis of “delusions of interpretation”, a concept that has since become famous in France but less well-accepted to psychiatry in the English-speaking world, emphasises what they call the “interpretative side” of psychosis over the paranoid or persecutory aspect.

With fine clinical observation, they focus on the role of interpretation in paranoia and conclude that the real kernel of paranoia is not ideas of persecution but an interpretative delusion. An interpretative delusion can be characterised in these terms. It begins with a dominant idea such as one of grandeur or persecution, or perhaps a mystical, erotic or jealous idea. There then ensues a reasoning and systematising process that successively crystallises a series of interpretations out of the phenomenon. Their analysis thus emphasises the role of the signifier itself, rather than the role of the signified or the content of the persecutory delusion.

Sérieux and Capgras contrast interpretative delusions (as the kernel of paranoia) with litigious delusions, taking the latter to be a distinct entity. Litigious delusions are linked to a precise external cause that the subject regards as prejudicial, and the subject is characterised by an idée fixe and by a manic commitment to working for “the cause”, as he understands it.

The task of separating out and refining these significant clinical entities was clearly an arduous business. The absence of hallucinations, mood disturbance, or signs of schizophrenia worried the authors to the point where they even wondered whether what they were describing really was a mental illness. And the precise identification of the interpretative delusion was difficult to make.

The article is accompanied by a valuable discussion of the strengths and weaknesses of Sérieux and Capgras’s contribution with Jacques-Alain Miller and other members of the École de la Cause freudienne.

Russell Grigg

[i] John Cutting and Michael Shepherd published a long excerpt from Les folies raisonnantes (pp. 5-43) in their excellent edited volume, The clinical roots of the schizophrenia concept (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1987), along with other seminal works from French and German psychiatrists.

The facets of jealousy

** *

SATURDAY 15th DECEMBER 2012

* * *

Morning Session

10.30 – 1.00

Workshop co-facilitated by Laure Naveau and Vincent Dachy

Bogdan Wolf: Jealousy and envy in Freud and Lacan

Véronique Voruz: 'Reading Catherine M. on Jealousy'

Laure Naveau: The other man of her life

* * *

Afternoon Session

14.30 – 17.00

Guest Speaker: Pierre Naveau

Psychoanalyst in Paris and member of the ECF and the NLS

‘Jealousy and the hidden gaze’

Betty Bertrand-Godfrey

Jealousy as a name of the Father?

Heather Chamberlain

How do we work with a jealous patient?

Chair: Roger Litten

** *

There will be ample time dedicated to discussion and the following readings are suggested:

Sigmund Freud

Some Neurotic Mechanisms in Jealousy, Paranoia and Homosexuality (1922)

Jacques Lacan

Family complexes in the Formation of the Individual (1938)

Seminar XX (1998)

Catherine Millet

Jour de souffrance (no English translation available)

Marcel Proust

Swann in love

The Captive

William Shakespeare

University of London Student Union

Bloomsbury Suite

Second Floor

Malet Street, London W1

£15/£10 Concessions

of public service the journal of the New Lacanian School is”

Éric Laurent

On Dominique Holvoet’s ‘The Pleasure of the Symptom‘

“Psychoanalysis specifies itself by renouncing the attempt to resolve discontent [malaise] by eradicating the symptom”.

“Mr B turned to psychoanalysis because of a somatic symptom that medicine had been unable to treat – a hypertension that, by this point, had become so crippling that, when he came to see me ten years ago, he had not been able to work for a year. He was, he said, constantly tense, stressed, and deeply angry. This anger is a sort of stifled rage”.

In this clinical case Dominique Holvoet gradually unfolds the scenes and the crucial encounters which established the structure of the subject, as well as the formula of the fantasy. This case is about a subject that responds as a wounded man each time the Other of demand appears: “if you want me to fall, there you are!”. Thus, he was captivated by an obsessional desire, the desire to kill desire – a death wish.

In the analytic experience “the symptom passes from its repetitive necessity … to the possibility of contingency, in other words the possibility of acknowledging the irreducible real of the symptom, offering a new trajectory for jouissance. The new status of the symptom, severed from meaning, the reconciliation with the real, opens to contingency. From this, a new responsibility is deduced for the analysand”.

The orientation of psychoanalysis is “… not to let oneself go on the side of meaning, but instead seek to make the well of meaning run dry in order get to the bone, which is the drive [pulsionnel]”.

Through this particular case, Dominique Holvoet designates the new status of the symptom, the symptomatic remainder after the revelation of the fantasy.

Despina Karagianni

The Psychotic Subject in the Geek Era

Typicality and Symptomatic Inventions

Argument

In a world where each “One” is kitted out with his “I-object”, a world where being a geek[1] constitutes an ordinary lifestyle, what becomes of what we call psychosis? The triumph of the “I-gadgets” as objects outside-the-body [hors-corps] has upset relations between parlêtres, relations that hitherto were codified by what Freud called the programme of civilisation. From the 20th to the 21st century, we have passed from the era of discourses that knot the social bond to the world of the One-all-alone which finds support in the symptom as an alternative social bond.

In his intervention at the Tel Aviv Congress, which will be the reference for the Congress in Athens, Éric Laurent proposes for the NLS “an enquiry into the way in which we read, in our present-day practice, what the word ‘psychosis’ means for psychoanalysis.”[2]. One can indeed generalise the psychotic effort, which consists in giving order to the world without the aid of established discourses, to the general effort of writing one’s own symptom. This symptomatic mark, this seal on the body, this trace of lalangue, or even forced invention, consists in a reduction of the flight of meaning. On the other side, surfing the frantic canvas of the web presents itself as the Danaids’ barrel of the 21st century. Thus, for Raffaele Simone, the mediasphere produces a revolution in the mind that is larger and more penetrating than the one feared by Plato in Phaedrus regarding the advent of writing[3]. Rather than adopting an attitude of nostalgic sorrow, we shall say how psychoanalysis takes on board these new forms of books, written in real-time, that each individual drafts in his own image, a private Facebook that is more and more open towards the world, an exhibition of one’s own case under constant revision. However, Simone stands closer to Lacan in so far as he considers that media are not man’s extension, but on the contrary, man is the media’s extension. Is not the “I-object” a supplementary organ whose function is sought by the bloggers we are?

In this context of great disorder in the real[4], psychiatry has increasingly distanced itself from the constituent signs of psychosis in favour of the silence of the organs (to the point of losing all references, for example, in the case of Anders Behring Breivik). Meanwhile, psychoanalysis, rather than mourn the decline of the paternal imago, has revealed the arbitrariness of the father, its fictional dimension, in order to focus more and more on the formal envelope of the symptom. This is how it aims at the symptom’s core of jouissance in what is most real about it, which constitutes at the same time, for the speaking-being, his most singular anchoring point.

Many discourses attempt to give order to the world. Lacan formalised four of them, plus the capitalist discourse “which gnaws away at each of them” and where “it is the object a that rises to the zenith and redistributes the possible permutations”[5]. The conceptual shift in Lacan’s work which moves from the first to the second paternal metaphor corresponds to this movement of civilisation that is becoming plural[6]. It is no longer just the Name-of-the-Father, but the whole of language that takes charge of phenomena in which signification is stabilised. This Other which Lacan barred with a stroke to mark that it only takes its assurance from a fiction, this Other which therefore does not exist, forces each of us to produce the singularity of our trajectory.

In the papers for the Congress we will have to emphasize the symptomatic invention, the singular subjective bricolage called upon by the era of the Other that does not exist[7] and its “I-objects”. In other words, how does the subject make a language out of his symptom? How does he grasp hold of objects to turn them into functional organs? Éric Laurent points this out: it is from the psychotic subject that we must learn how, for each and every one of us, the whole of language takes charge of the effort of naming jouissance. Thus, the right way to be a heretic in psychoanalysis after Oedipus[8] would be “the one that, from having recognised the nature of the sinthome, does not hesitate to use it logically, that is to say, to use it until he reaches his real, after which his thirst is sated.”[9] To recognise the nature of the sinthome is to recognise the way in which “enjoying substance is taken up in language itself” and given order[10]. It is the language-organ that makes a subject a parlêtre, implying that at the same time as it gives him being it fobs him off with a having, his body. By significantizising them, organ-language plies the organs out of the body, which makes them problematic and requires that a function be found for them, without the aid of any established discourse, for the so-called schizophrenic.[11].

We can thus make the catalogue of psychotic inventions[12]: invention of a discourse, of a resource to be able to make use of his body in the case of the schizophrenic, invention of a relation to the Other to stay in the social bond in the case of the paranoiac, impossible invention in the case of the melancholic, invention of an anchoring point or an identification in the cases of ordinary psychosis. Furthermore, non-invention constitutes an equally interesting class, as the trauma of language appears there in its purity.

Our effort, says É. Laurent, is however the reverse of classificatory attempts. There is in psychoanalysis a horizon of the unclassifiable at which this effort aims, so that the symptom may designate the singularity of a subject. But this extension to the ordinary status of psychosis to “everyone is mad”, does not mean that everyone is psychotic. “One should not mix up the lessons to be learnt from the psychotic subject (which bear on the entirety of the clinical field) with a clinical category as such, making it the most sizeable category of our experience.”[13]. Thus, our enquiry should also explore “how the ordinary Name-of-the-Father of existence transforms once we have our horizon of the unclassifiable”[14]. And we shall find once again, with the dimension of the father as fiction, the typicality of psychosis, and the phenomena of triggering linked to the encounter with “A-father”, phenomena which do not concern invention.

Ordinary delusion is a geek’s effort of invention. “You can be sure that it’s a delusion when it stays at the level of One-by-himself […] Does it manage to form a social bond or not? Sometimes contingency plays a role. There are forms of delusion that one can clearly see cannot be socialized”[15]. But don’t religious fanaticism, authoritarian therapies, or even generalised evaluation, reveal a furious call to the father? To these triumphant forms of the collective, doesn’t psychoanalysis oppose an unheard-of response in so far as it is an experience of traversing the impasses of the “One-all-alone”? This is the question that our enquiry on psychosis in the geek era may contribute to solve.

Dominique Holvoet

Translated by Florencia Fernandez Coria Shanahan

[1] Geek: American slang term that originally referred to a person considered odd, perceived as overly intellectual. Gradually used more internationally on the Internet, the term is claimed by proponents of high-tech gadgets. According to the Oxford American Dictionary, the origin of the word is the Middle High German Geck, which means a fool, a mischievous, and the Dutch Gek which designates something crazy. (Source : Wikipedia)

[2] Laurent E., «Psychosis, or Radical Belief in the Symptom», Hurly-Burly Issue 8, October 2012, p. 243.

[3] Simone R., Pris dans la toile, l’esprit aux temps du web, Gallimard, French translation to be published on November 15th 2012. Original version in Italian: Presi nella rete. La mente ai tempi del web, Saggi, avril 2012.

[4] Reference to the title of the forthcoming WAP Congress in Paris in 2014. Conference by J-A Miller published in Lacan Quotidien 63, available on the NLS website.

[5] Laurent É. op. cit. p. 244.

[6] Miller J-A, Extimity, Course of 5th February 1986.

[7]Miller J-A, «Psychotic Invention», Hurly Burly Issue 8, October 2012, p. 263: «The Other doesn’t exist means that the subject is conditioned to becoming an inventor».

[8] Caroz G., See his excellent argument for PIPOL 6, «After Oedipus». The NLS Congress in Athens is thus inscribed within the perspective of the 2nd European Congress of Psychoanalysis, organised by the EuroFederation on July 6th and 7th 2013. (www.europsychoanalysis.eu)

[9] Lacan J., Le Séminaire, Livre XXIII, Le sinthome, (1975-1976), Paris, Seuil, 2005, p. 15.

[10] Laurent É., op. cit. p. 247.

[11] Lacan J., «L’étourdit» (1972), Autres écrits, Seuil, 2001, p. 474. «… from this real: that there is no sexual relation, by dint of the fact that an animal has a stabitat that is language, that dicking around in it [labiter] is likewise what forms an organ for his body – an organ which, so as to ex-sist unto him in this way, determines it from its function, and this happens even before he finds its function. It is even on this basis that he is reduced to finding that his body is not without other organs, and that the function they each hold poses a problem for him – which specifies the so-called schizophrenic [le dit schizophrène] on account of being caught without the aid of any established discourse.»

[12] Miller J.-A., «Psychotic Invention», Hurly-Burly Issue 8, October 2012.

[13] Laurent E., op. cit. p. 249.

[14] Laurent E., op. cit.

[15] Miller J.-A., op. cit., p. 268.

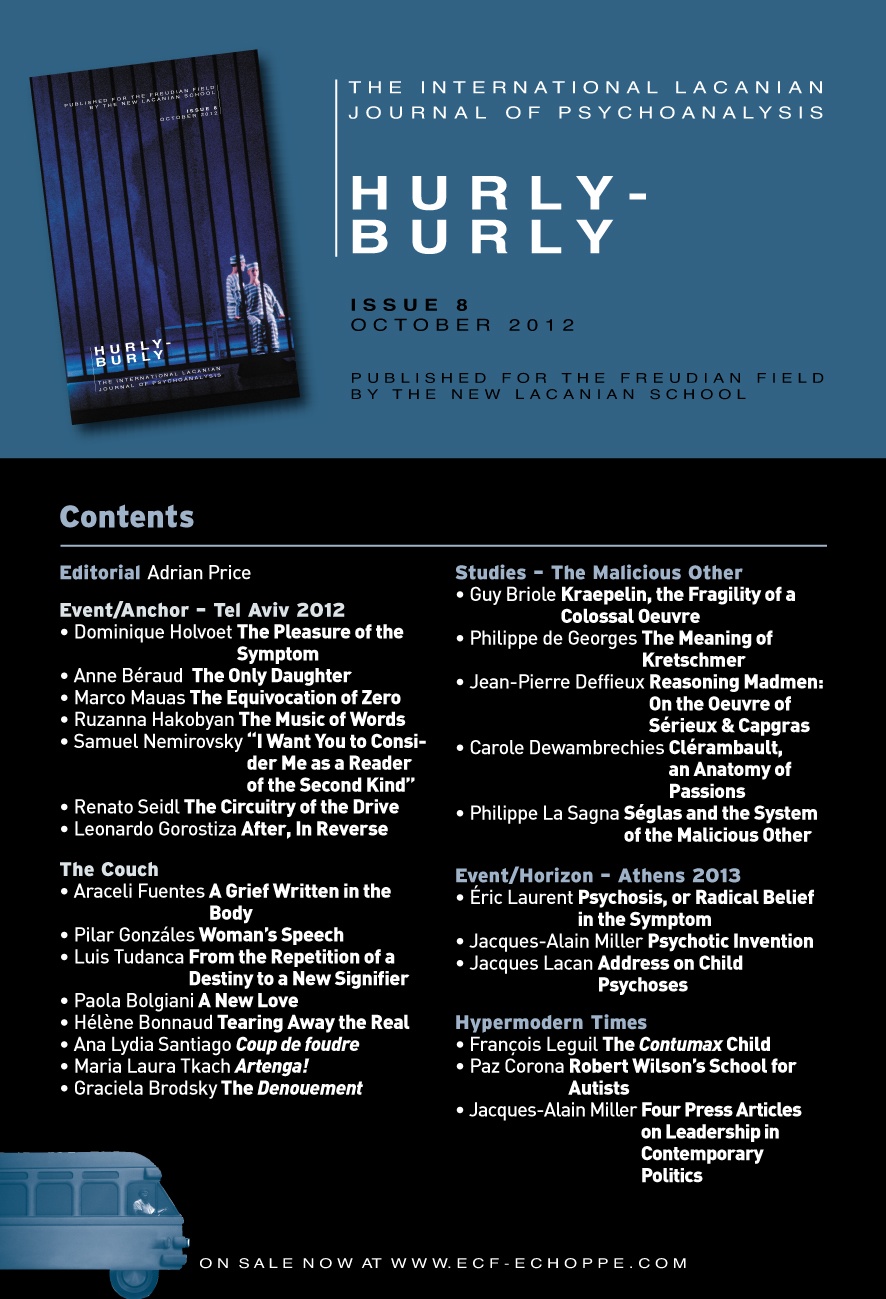

Il peut être acheté pour Kr 150 plus frais postaux, en communiquant avec l’éditeur: info (@) forlagetspring.dk

of public service the journal of the New Lacanian School is”

The Contumax Child , by Francois Leguil

“[…] Lacan enters the debate opened by the first page of the Antimemoirs as someone who is very well informed. Although we shall have to come back to the invigorating nature of Lacan ’s critique, we may note that there is an indisputable moral integrity when, “hystericising” his own stance, Malraux asks, exhausted by his uncommon ordeals: “What is a man?”, because he doesn’t content himself with simply saying that it’s not the same thing as a grown-up. By default, Malraux deserves credit for not proposing that a man is a father and that being a father means having children.

Since being a father is not a matter of knowing how to have children, does it mean knowing how to face up to the idea of losing them? This is not a way of getting out of this serious issue by some intellectual pirouette. Rather it takes us back to a long tradition that stretches from Golgotha to the nation’s sacrifice of its sons as inscribed on the monuments to the fallen. Recall if you will, although developing it here would lead us too far off track, that what Lacan had already been diagnosing before the war as the “decline of the father”[1] does not sit in the same line as this tradition which ultimately does no more than pass the consequences of the paternal metaphor onto the child, and does so because the Name-of-the-Father is a dead father. Lacan’s commentary in his Seminar on the famous Freudian dream, “Father, can’t you see that I’m burning?”, does not go in the direction of an exploitation of pathos, but rather turns towards the enigma of the desire of the Other.[2]”

Francois Leguil raises questions about what constitutes a grown up, a child, a man and a father. These concepts, that are etymologically simple, are semantically charged and complicated. From Freud to Lacan, from religion to psychoanalysis, the author of the text attempts to answer some crucial existential questions “of being”.

Stella Steletari

[1] Cf. Lacan, J., “Les Complexes familiaux dans la formation de l’individu”, in Autres écrits, Seuil, Paris, 2001, p. 60: “a social decline of the paternal imago”.

[2] Lacan, J., The Seminar, Book XI, The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, transl. by A. Sheridan, Penguin, 1994, pp. 57-60.

SOCIÉTÉ

HELLÉNIQUE – NLS

Séminaire

Nouages à Athènes

Samedi,

le 22 septembre 2012

Rapport

Par

Despina Karagianni

Dominique

Holvoet,

président de la NLS, était l’intervenant principal du

séminaire

Nouages qui a eu lieu à Athènes le 22 septembre 2012.

Sa

présentation était

une introduction permettant d’orienter nos travaux en vue

du XIe

Congrès de la NLS qui aura lieu à Athènes, les 18 et 19

mai 2013.

Dominique

Holvoet a fait

le lien entre le congrès précédent (Lire un symptôme)

et

le prochain (dont le titre provisoire était : La

Psychanalyse et le sujet psychotique : De l’invention

forcée

à la croyance au symptôme ;

et le titre définitif est : Le sujet

psychotique à

l’époque Geek :

typicité

et inventions symptomatiques).

Les points

principaux de

sa présentation se résument ainsi :

L’articulation

des deux

termes, Psychanalyse et Psychose doit être effectuée sur

la base

d’un renversement de perspective dans la psychanalyse qui

émerge

dans une série de substitutions.

La première

concerne la

substitution du terme d’« interprétation » par celui

de « lecture » du symptôme et est exprimée à travers

un déplacement de la clinique vers une nouvelle

orientation

« Au-delà du sens », au niveau de la matérialité de la

lettre.

Une

nouvelle substitution par le terme de « constat » vient

viser la marque du signifiant sur le corps. Cette marque

concerne le

moment mythique où le signifiant percute le corps1.

Nos

travaux « vers Athènes » vont

prendre la forme d’une enquête autour de la question

suivante :

quelles sont les conséquences d’un tel renversement de

perspective

au sujet de la psychose ?

La

psychanalyse n’envisage pas la psychose comme une

catégorie

distincte, mais elle s’intéresse à la manière dont

chaque sujet,

s’appuyant sur son symptôme, s’insère dans la

civilisation.

Cette insertion présuppose, d’une part, la capacité de

l’usage

d’une langue commune qui garantit le lien social, et,

d’autre

part, une langue privée constituée par l’écriture du

symptôme2

Chez Freud,

l’universalité de l’Œdipe était posée comme un « appareil

civilisateur » qui réglait les jouissances à l’aide de

l’interdiction. À cette époque la figure paternelle avait

déjà

commencé à s’ébranler. La psychanalyse se déplace alors de

la

dimension du conflit psychique vers l’enveloppe

formelle

du symptôme comme mode de traitement de la pulsion.

Pendant la

période

classique de Lacan, la valeur symbolique de la figure

paternelle est

relevée. La fonction de la métaphore paternelle règle la

jouissance et stabilise les significations en leur donnant

une valeur

phallique. L’échec de cette fonction fait que le sujet ne

peut pas

trouver refuge dans la langue pour régler les phénomènes

de

jouissance. Les conséquences qui en résultent agissent non

seulement sur le corps mais sur le code même de la langue,

en le

transformant en un néo-code.

Jacques-Alain

Miller

pointe une deuxième métaphore dans laquelle la figure

paternelle

donne sa place au Nom-du-Père, un signifiant qui peut être

remplacé

par d’autres signifiants maîtres. La psychose est

caractérisée

par une jouissance qui n’arrive pas à passer « toute »

sous le régime du Nom-du-Père. Lacan la nomme « non

négativable ».

On

remarque donc que l’Autre de la deuxième métaphore

n’est pas de

l’ordre du Un, il est au contraire barré,

inconsistant. Lacan

propose l’écriture :

, un mathème3

qui peut également s’écrire ainsi : Α

barré

/ –φ.

Dominique Holvoet propose une écriture plus simplifiée

du A barré

/ –φ :

A barré / j.

Nous

passons du Nom-du-Père comme Autre consistant à sa

pluralité. Par

conséquent, il y a plusieurs façons de significantiser

la

jouissance, et non pas uniquement la façon paternelle.

Alors que

chez le Lacan classique, le traitement du réel se

faisait à partir

du signifiant, ce traitement est désormais attendu de

l’ensemble

du champ de la langue. En fait il semblerait que ce

soit le réel qui

traite le signifiant, une constatation qui conduira

Lacan à faire de

la langue un organe.

Dans

l’Étourdit

nous lisons : « du fait qu’un animal à stabitat qu’est

le

langage, que de

labiter, c’est aussi bien ce qui pour son corps fait

organe –

organe qui pour ainsi lui ex-sister, le détermine de

sa fonction, ce

dès avant qu’il la trouve. C’est même de là qu’il est

réduit

à trouver que son corps n’est pas sans autres organes,

et que leur

fonction à chacun, lui fait problème, – ce dont le dit

schizophrène

se spécifie d’être pris sans le secours d’aucun

discours

établi. »4

Dans la

mesure où

l’Autre n’existe pas, cet Autre n’est donc qu’une

invention.

Une cure psychanalytique consiste en cette invention. La

psychanalyse

ne concerne plus la production de significations, mais

plutôt une

réconciliation avec notre langue privée, avec l’Autre que

nous

avons inventé. Le sujet est poussé à faire de la langue

son

instrument, à bricoler.

On

pourrait résumer ainsi les deux périodes de Lacan – de

la première à la deuxième métaphore :

|

Lacan

Question préliminaire à |

Dernier

Subversion du sujet et |

|

Interprétation Désir |

Constat Jouissance |

|

Le Réel est

Le |

Le

La Lettre Le Réel |

|

L’Ordre |

|

|

Les |

Le Bricolage |

|

Le |

Le Symptôme |

La

croyance au symptôme,

une formulation d’Éric Laurent, concerne une invention

forcée.

Cependant, tous les sujets ne disposent pas des discours

établis

pour appuyer leur invention. Dominique Holvoet pose une

série de

questions qui doivent être

considérées

en vue de notre recherche sur la psychose : dans quelle

mesure

doit-on croire à son symptôme pour que celui-ci puisse

fonctionner ? Qu’en est-il du Nom-du-Père dans la psychose

ordinaire, un cas de psychose dont il s’agit de tirer les

leçons

sans la généraliser pour tous ? Comment se transforme le

Nom-du-Père chez le sujet contemporain ? Enfin, comment le

Nom-du-Père continue de fonctionner alors qu’il est plus

ordinaire?

Le rôle du

psychanalyste

est fondamental : il doit constituer une borne à l’errance

du

sujet psychotique. Tandis que le psychanalyste a perçu

l’inexistence

de l’Autre, il s’en sert comme instrument. Dominique

Holvoet

conclut que, dans une analyse, il ne s’agit pas de tuer le

père

– cela ne conduirait absolument pas à la mort de la

libido.

Ce que Lacan appelait « psychanalyse pure » demande tout

d’abord la réduction du père à la dimension du semblant

et, par

la suite, faire de même pour le discours de l’analysant.

Ceci mène

à une invention qui constitue la dignité d’un symptôme

irréductible.

_________________________________________________________________

Dans la

partie clinique

du Séminaire, Zvili Cohen, psychologue, membre du GIEP

(Israël) de

la NLS, a présenté le premier cas clinique, avec le titre

« Trop

peu, trop tard – traces du temps ».

Il s’agit

d’une femme

dont le symptôme principal est sa difficulté à gérer et à

calculer le temps. Être la fille aux yeux de sa mère

constituait

une sorte de compensation imaginaire pour elle. Après la

mort de sa

mère, un chien a pris la place du substitut phallique et

de cette

manière une stabilité rudimentaire a été obtenue. Après la

mort

du chien, la patiente a commencé à souffrir de quelque

chose

qu’elle appelait une « dépression ». Des années

après, quand elle a été confrontée à la mort de son

deuxième

chien ainsi qu’à son incapacité d’être mère, elle a

commencé

une psychothérapie.

Tout au long

de sa vie le

sujet était submergé par la jouissance du « mort-vivant ».

Elle oscillait. Son rapport symptomatique avec le

temps est

lié à sa rivalité avec sa belle-mère, la présence de

laquelle

cause une sorte d’hémorragie de l’héritage maternel et par

conséquent du sujet lui-même. Il semble que le

psychanalyste

fonctionne comme un pilier pour le sujet. Les

séances

prennent le statut d’une ponctuation dans l’oscillation

dans le

temps.

___________________________________________________________________

Le deuxième

cas clinique

portant le titre « Ulysse ou l’artiste et son

objet » a été présenté par Hélène Molari,

psychiatre,

praticien hospitalier à l’Hôpital psychiatrique d’Attique

et

membre de la Société hellénique de la NLS. Dans ce cas, il

s’agissait d’un sujet maniaque qui avait été hospitalisé

et

était suivi par la thérapeute depuis son hospitalisation.

Hélène Molari

a d’abord

esquissé la phénoménologie du cas clinique selon

Kraepelin. Par la

suite, elle a présenté la construction de la problématique

subjective par rapport à l’objet selon Lacan.

Le sujet

était stabilisé

jusqu’à l’âge de 40 ans ayant comme soutiens imaginaires

son

père et son art puisqu’il était scénographe et peintre.

L’invasion de la technologie digitale dans le champ de

l’art

ainsi qu’une certaine confrontation avec son père, ont été

un

coup pour lui et l’ont amené à dévaloriser les seules

solutions

qu’il avait.

Dans ce cas

clinique,

l’échec de l’objet a à condenser la jouissance,

laisse

le sujet exposé à une interminable métonymie de la chaîne

signifiante et à une excitation sans limites du corps. Le

thérapeute, étant l’Autre qui n’exige pas mais garantit

l’ordre

des choses, accompagne le sujet dans son effort à créer un

sinthome

de sorte que le signifiant et la jouissance arrivent à

coexister

dans le lien social. Du moment que le sujet a à sa

disposition un

répertoire d’objets réels, la création artistique

fonctionne de

façon à limiter la jouissance à travers la ponctuation

d’une

nomination.

Bibliographie

française

Lacan

J., « Question préliminaire à tout traitement possible de

la

psychose » (1958), Écrits, Paris, 1966, p. 557.

Lacan

J., « Subversion du sujet et dialectique du désir »,

Écrits, Paris, 1960, p. 819.

Miller

J.-A., « L’invention psychotique », Quarto no

80/81, 2004, p. 6-13.

Bibliographie

anglaise

Lacan,

J., (2006). On a Question Prior to Any Possible

Treatment of

Psychosis (1958). Ecrits. Norton, pp.

464.

Lacan, J.,

(2006).

The Subversion of the Subject and the Dialectic of Desire

(1960).

Ecrits. Norton, pp. 694.

1 Le corps doit être conçu ici comme un

ensemble d’organes dont la fonction est à trouver.

2 Le symptôme est à entendre comme lien social

alternatif.

3 Lacan J., « Subversion du sujet et

dialectique du désir », Écrits, éd. du

Seuil, Paris, 1960, p. 819

4 Lacan J.,

« L’étourdit », Autres Ecrits, éd. du

Seuil, Paris, 2001, p. 474.

SOCIÉTÉ

HELLÉNIQUE – NLS

Séminaire

Nouages à Athènes

Samedi,

le 22 septembre 2012

Rapport

Par

Despina Karagianni

Dominique

Holvoet,

président de la NLS, était l’intervenant principal du

séminaire

Nouages qui a eu lieu à Athènes le 22 septembre 2012.

Sa

présentation était

une introduction permettant d’orienter nos travaux en vue

du XIe

Congrès de la NLS qui aura lieu à Athènes, les 18 et 19

mai 2013.

Dominique

Holvoet a fait

le lien entre le congrès précédent (Lire un symptôme)

et

le prochain (dont le titre provisoire était : La

Psychanalyse et le sujet psychotique : De l’invention

forcée

à la croyance au symptôme ;

et le titre définitif est : Le sujet

psychotique à

l’époque Geek :

typicité

et inventions symptomatiques).

Les points

principaux de

sa présentation se résument ainsi :

L’articulation

des deux

termes, Psychanalyse et Psychose doit être effectuée sur

la base

d’un renversement de perspective dans la psychanalyse qui

émerge

dans une série de substitutions.

La première

concerne la

substitution du terme d’« interprétation » par celui

de « lecture » du symptôme et est exprimée à travers

un déplacement de la clinique vers une nouvelle

orientation

« Au-delà du sens », au niveau de la matérialité de la

lettre.

Une

nouvelle substitution par le terme de « constat » vient

viser la marque du signifiant sur le corps. Cette marque

concerne le

moment mythique où le signifiant percute le corps1.

Nos

travaux « vers Athènes » vont

prendre la forme d’une enquête autour de la question

suivante :

quelles sont les conséquences d’un tel renversement de

perspective

au sujet de la psychose ?

La

psychanalyse n’envisage pas la psychose comme une

catégorie

distincte, mais elle s’intéresse à la manière dont

chaque sujet,

s’appuyant sur son symptôme, s’insère dans la

civilisation.

Cette insertion présuppose, d’une part, la capacité de

l’usage

d’une langue commune qui garantit le lien social, et,

d’autre

part, une langue privée constituée par l’écriture du

symptôme2

Chez Freud,

l’universalité de l’Œdipe était posée comme un « appareil

civilisateur » qui réglait les jouissances à l’aide de

l’interdiction. À cette époque la figure paternelle avait

déjà

commencé à s’ébranler. La psychanalyse se déplace alors de

la

dimension du conflit psychique vers l’enveloppe

formelle

du symptôme comme mode de traitement de la pulsion.

Pendant la

période

classique de Lacan, la valeur symbolique de la figure

paternelle est

relevée. La fonction de la métaphore paternelle règle la

jouissance et stabilise les significations en leur donnant

une valeur

phallique. L’échec de cette fonction fait que le sujet ne

peut pas

trouver refuge dans la langue pour régler les phénomènes

de

jouissance. Les conséquences qui en résultent agissent non

seulement sur le corps mais sur le code même de la langue,

en le

transformant en un néo-code.

Jacques-Alain

Miller

pointe une deuxième métaphore dans laquelle la figure

paternelle

donne sa place au Nom-du-Père, un signifiant qui peut être

remplacé

par d’autres signifiants maîtres. La psychose est

caractérisée

par une jouissance qui n’arrive pas à passer « toute »

sous le régime du Nom-du-Père. Lacan la nomme « non

négativable ».

On

remarque donc que l’Autre de la deuxième métaphore

n’est pas de

l’ordre du Un, il est au contraire barré,

inconsistant. Lacan

propose l’écriture :

, un mathème3

qui peut également s’écrire ainsi : Α

barré

/ –φ.

Dominique Holvoet propose une écriture plus simplifiée

du A barré

/ –φ :

A barré / j.

Nous

passons du Nom-du-Père comme Autre consistant à sa

pluralité. Par

conséquent, il y a plusieurs façons de significantiser

la

jouissance, et non pas uniquement la façon paternelle.

Alors que

chez le Lacan classique, le traitement du réel se

faisait à partir

du signifiant, ce traitement est désormais attendu de

l’ensemble

du champ de la langue. En fait il semblerait que ce

soit le réel qui

traite le signifiant, une constatation qui conduira

Lacan à faire de

la langue un organe.

Dans

l’Étourdit

nous lisons : « du fait qu’un animal à stabitat qu’est

le

langage, que de

labiter, c’est aussi bien ce qui pour son corps fait

organe –

organe qui pour ainsi lui ex-sister, le détermine de

sa fonction, ce

dès avant qu’il la trouve. C’est même de là qu’il est

réduit

à trouver que son corps n’est pas sans autres organes,

et que leur

fonction à chacun, lui fait problème, – ce dont le dit

schizophrène

se spécifie d’être pris sans le secours d’aucun

discours

établi. »4

Dans la

mesure où

l’Autre n’existe pas, cet Autre n’est donc qu’une

invention.

Une cure psychanalytique consiste en cette invention. La

psychanalyse

ne concerne plus la production de significations, mais

plutôt une

réconciliation avec notre langue privée, avec l’Autre que

nous

avons inventé. Le sujet est poussé à faire de la langue

son

instrument, à bricoler.

On

pourrait résumer ainsi les deux périodes de Lacan – de

la première à la deuxième métaphore :

|

Lacan

Question préliminaire à |

Dernier

Subversion du sujet et |

|

Interprétation Désir |

Constat Jouissance |

|

Le Réel est

Le |

Le

La Lettre Le Réel |

|

L’Ordre |

|

|

Les |

Le Bricolage |

|

Le |

Le Symptôme |

La

croyance au symptôme,

une formulation d’Éric Laurent, concerne une invention

forcée.

Cependant, tous les sujets ne disposent pas des discours

établis

pour appuyer leur invention. Dominique Holvoet pose une

série de

questions qui doivent être

considérées

en vue de notre recherche sur la psychose : dans quelle

mesure

doit-on croire à son symptôme pour que celui-ci puisse

fonctionner ? Qu’en est-il du Nom-du-Père dans la psychose

ordinaire, un cas de psychose dont il s’agit de tirer les

leçons

sans la généraliser pour tous ? Comment se transforme le

Nom-du-Père chez le sujet contemporain ? Enfin, comment le

Nom-du-Père continue de fonctionner alors qu’il est plus

ordinaire?

Le rôle du

psychanalyste

est fondamental : il doit constituer une borne à l’errance

du

sujet psychotique. Tandis que le psychanalyste a perçu

l’inexistence

de l’Autre, il s’en sert comme instrument. Dominique

Holvoet

conclut que, dans une analyse, il ne s’agit pas de tuer le

père

– cela ne conduirait absolument pas à la mort de la

libido.

Ce que Lacan appelait « psychanalyse pure » demande tout

d’abord la réduction du père à la dimension du semblant

et, par

la suite, faire de même pour le discours de l’analysant.

Ceci mène

à une invention qui constitue la dignité d’un symptôme

irréductible.

_________________________________________________________________

Dans la

partie clinique

du Séminaire, Zvili Cohen, psychologue, membre du GIEP

(Israël) de

la NLS, a présenté le premier cas clinique, avec le titre

« Trop

peu, trop tard – traces du temps ».

Il s’agit

d’une femme

dont le symptôme principal est sa difficulté à gérer et à

calculer le temps. Être la fille aux yeux de sa mère

constituait

une sorte de compensation imaginaire pour elle. Après la

mort de sa

mère, un chien a pris la place du substitut phallique et

de cette

manière une stabilité rudimentaire a été obtenue. Après la

mort

du chien, la patiente a commencé à souffrir de quelque

chose

qu’elle appelait une « dépression ». Des années

après, quand elle a été confrontée à la mort de son

deuxième

chien ainsi qu’à son incapacité d’être mère, elle a

commencé

une psychothérapie.

Tout au long

de sa vie le

sujet était submergé par la jouissance du « mort-vivant ».

Elle oscillait. Son rapport symptomatique avec le

temps est

lié à sa rivalité avec sa belle-mère, la présence de

laquelle

cause une sorte d’hémorragie de l’héritage maternel et par

conséquent du sujet lui-même. Il semble que le

psychanalyste

fonctionne comme un pilier pour le sujet. Les

séances

prennent le statut d’une ponctuation dans l’oscillation

dans le

temps.

___________________________________________________________________

Le deuxième

cas clinique

portant le titre « Ulysse ou l’artiste et son

objet » a été présenté par Hélène Molari,

psychiatre,

praticien hospitalier à l’Hôpital psychiatrique d’Attique

et

membre de la Société hellénique de la NLS. Dans ce cas, il

s’agissait d’un sujet maniaque qui avait été hospitalisé

et

était suivi par la thérapeute depuis son hospitalisation.

Hélène Molari

a d’abord

esquissé la phénoménologie du cas clinique selon

Kraepelin. Par la

suite, elle a présenté la construction de la problématique

subjective par rapport à l’objet selon Lacan.

Le sujet

était stabilisé

jusqu’à l’âge de 40 ans ayant comme soutiens imaginaires

son

père et son art puisqu’il était scénographe et peintre.

L’invasion de la technologie digitale dans le champ de

l’art

ainsi qu’une certaine confrontation avec son père, ont été

un

coup pour lui et l’ont amené à dévaloriser les seules

solutions

qu’il avait.

Dans ce cas

clinique,

l’échec de l’objet a à condenser la jouissance,

laisse

le sujet exposé à une interminable métonymie de la chaîne

signifiante et à une excitation sans limites du corps. Le

thérapeute, étant l’Autre qui n’exige pas mais garantit

l’ordre

des choses, accompagne le sujet dans son effort à créer un

sinthome

de sorte que le signifiant et la jouissance arrivent à

coexister

dans le lien social. Du moment que le sujet a à sa

disposition un

répertoire d’objets réels, la création artistique

fonctionne de

façon à limiter la jouissance à travers la ponctuation

d’une

nomination.

Bibliographie

française

Lacan

J., « Question préliminaire à tout traitement possible de

la

psychose » (1958), Écrits, Paris, 1966, p. 557.

Lacan

J., « Subversion du sujet et dialectique du désir »,

Écrits, Paris, 1960, p. 819.

Miller

J.-A., « L’invention psychotique », Quarto no

80/81, 2004, p. 6-13.

Bibliographie

anglaise

Lacan,

J., (2006). On a Question Prior to Any Possible

Treatment of

Psychosis (1958). Ecrits. Norton, pp.

464.

Lacan, J.,

(2006).

The Subversion of the Subject and the Dialectic of Desire

(1960).

Ecrits. Norton, pp. 694.

1 Le corps doit être conçu ici comme un

ensemble d’organes dont la fonction est à trouver.

2 Le symptôme est à entendre comme lien social

alternatif.

3 Lacan J., « Subversion du sujet et

dialectique du désir », Écrits, éd. du

Seuil, Paris, 1960, p. 819

4 Lacan J.,

« L’étourdit », Autres Ecrits, éd. du

Seuil, Paris, 2001, p. 474.

|

|

||||

Le sujet psychotique à l’époque Geek

Typicité et inventions symptomatiques

|

The Psychotic Subject in the Geek Era

Typicality and Symptomatic Inventions

|

|||

Bibliographie pour le Congrès de la NLS

|

Bibliography for the NLS Congress

|

|||

–

|

–

|

|||

–

|

–

|

|||

–

|

–

|

|||

–

|

–

|

|||

–

|

–

|

|||

–

|

–

|

|||

–

|

–

|

|||

–

|

–

|

|||

–

|

–

|

|||

–

|

–

|

|||

–

|

–

|

|||

–

|

– Miller,

|

|||

–

|

–

|

|||

–

|

–

|

|||

–

|

–

|

|||

–

|

–

|

|||

–

|

–

|

|||

–

|

–

|

|||

–

|

–

|

|||

–

|

–

|

|||

–

|

–

|

|||

–

|

–

|

|||

–

|

–

|

|||

–

|

Freud,

|

|||

–

|

–

|

|||

–

|

–

|

|||

–

|

–

|

|||

–

|

– Caroz,

|

|||

–

|

–

|

|||

–

|

–

|

|||

–

|

–

|

|||

–

|

–

|

|||

–

|

–

|

|||

–

|

–

|

|||